Gamble Family Reunion in South Carolina

My first DNA travel to where some of my enslaved ancestors were held.

At the beginning of August, my biological uncle Robert and I attended the 2022 Gamble family reunion, held in Charleston, South Carolina. Black Gamble descendants have been meeting annually since the 1970s, in different places around the country. We felt lucky to be able to go to this one in South Carolina since it included a trip to the small rural crossroads town of Nesmith, about an hour and a half north of Charleston in Williamsburg County. Nesmith was where our enslaved ancestors were held by the white Gamble family; this would be my very first time traveling to a place where some of my biological ancestors lived.

We initially had a lovely 3 day stay in historic downtown Charleston, in a beautiful rental co-owned by Karen Parson, the delightful owner of Parson Inn. One of my priorities during my genealogical travels is to support BIPOC-woman-owned businesses, like Karen’s. She has done an amazing job of saving and restoring historic homes in what was historically a Black community during legalized segregation and after. I loved meeting Karen and seeing the important work she is doing and the beautiful spaces she has created. If you are headed to Charleston I highly recommend booking a stay with her.

Our 3 bedroom unit, across the street from the Parson Inn, had beautiful, ornate details, hardwood floors, a stately fireplace in the living room, spacious and comfortable bedrooms with adjoining bathrooms, and a huge kitchen with all the amenities. It’s very centrally located near the Medical University of South Carolina and not far from the College of Charleston. It was perfect as our cousin Bobbi and her husband drove from Georgia to spend a few days with us– we made great use of all three bedrooms.

I loved exploring the neighborhood and taking in the Charleston architecture, which was directly influenced by Barbados architectural styles – very unique in character with porches running down the sides of houses, instead of on the front. There was a certain charm and Southern aesthetic to the city that I hadn’t experienced before. I also quickly learned that right below its beautiful exterior is a deeply disturbing and ugly history. The ornate and beautiful architecture is inexorably tied to the slave trade and rice plantation industry, both of which made Charleston the richest city in the country for many decades.

During those first few days, we all went on an incredible 2.5 hour Charleston Black History tour given by Al Miller of Sites and Insight Tours. We drove by plantations, an old sacred burial site for African slaves, and stopped to visit the stunningly beautiful and immense 400 year old Angel Oak Tree.

We then drove onto some of the local sea islands and saw black churches that have been there for centuries. We crossed bridges over the beautiful lush sea grasses that the Gullah Geechee people use to make baskets, using the same basketry art that was brought from Africa by their ancestors. I now understand how strongly Gullah culture is connected to African culture – even after more than 400 years. They are still considered the most Africanized or Black culture group in the United States.

So many African Americans can trace their roots back to South Carolina. My uncle and I do, not only through the Gamble family, but also my grandmother’s maternal line – which African Ancestry DNA testing shows had to have included a Mende or Temne tribal woman from present-day Sierra Leone. There is a very strong connection between South Carolina and the wider West African region that stretches from Senegal to Sierra Leone, as the Gullah Geechee culture most closely resembles Mende culture (Watch the documentaries Family Across the Sea and/or The Language You Cry In for more about this connection).

As I heard about the Gullah people, took in the passing landscape, saw the plantations, and felt the profound southern heat, I started to more deeply understand where I come from, and my inextricable ties to South Carolina. As we drove by the communities on the sea island that day, I was struck by how people have remained there on inherited land passed down family to family, connected to their history. And I felt grateful to finally be connecting to mine.

We finished the tour back in historic Charleston, learning about people important to local Black history and hearing the fascinating (and often disturbing) stories behind the beautiful buildings. Many of the homes still have the original slave quarters visible in the back. There was a particular home that had terrifying spikes on their wrought iron fence to keep Black people out. At one point in the seventeenth century, the population in Charleston was 4:1 Blacks to Whites, so there was a constant fear of slave uprisings.

Towards the end of the tour we stopped at the Battery, which is the waterfront fort looking out across the Atlantic. You can’t see Africa, but you know it’s there. It hit me how many people were shackled and brought here, including my ancestor, the Mende woman, whose name I will never know. My uncle and I were silent looking out over the water. What do you say while contemplating the devastation and brutality that your ancestral family members had to endure?

The next day we spent our last afternoon in old Charleston at the Avery Research Center for African American History and Culture, where I did some genealogy research and interviewed Erica Veal, Research Archivist and Interpretation Coordinator, about Black history in Charleston. The center’s mission is to collect, preserve and promote the history of the African Diaspora with a focus on the South Carolina Low Country. You can listen to the informal, yet extremely informative interview in my latest audio newsletter.

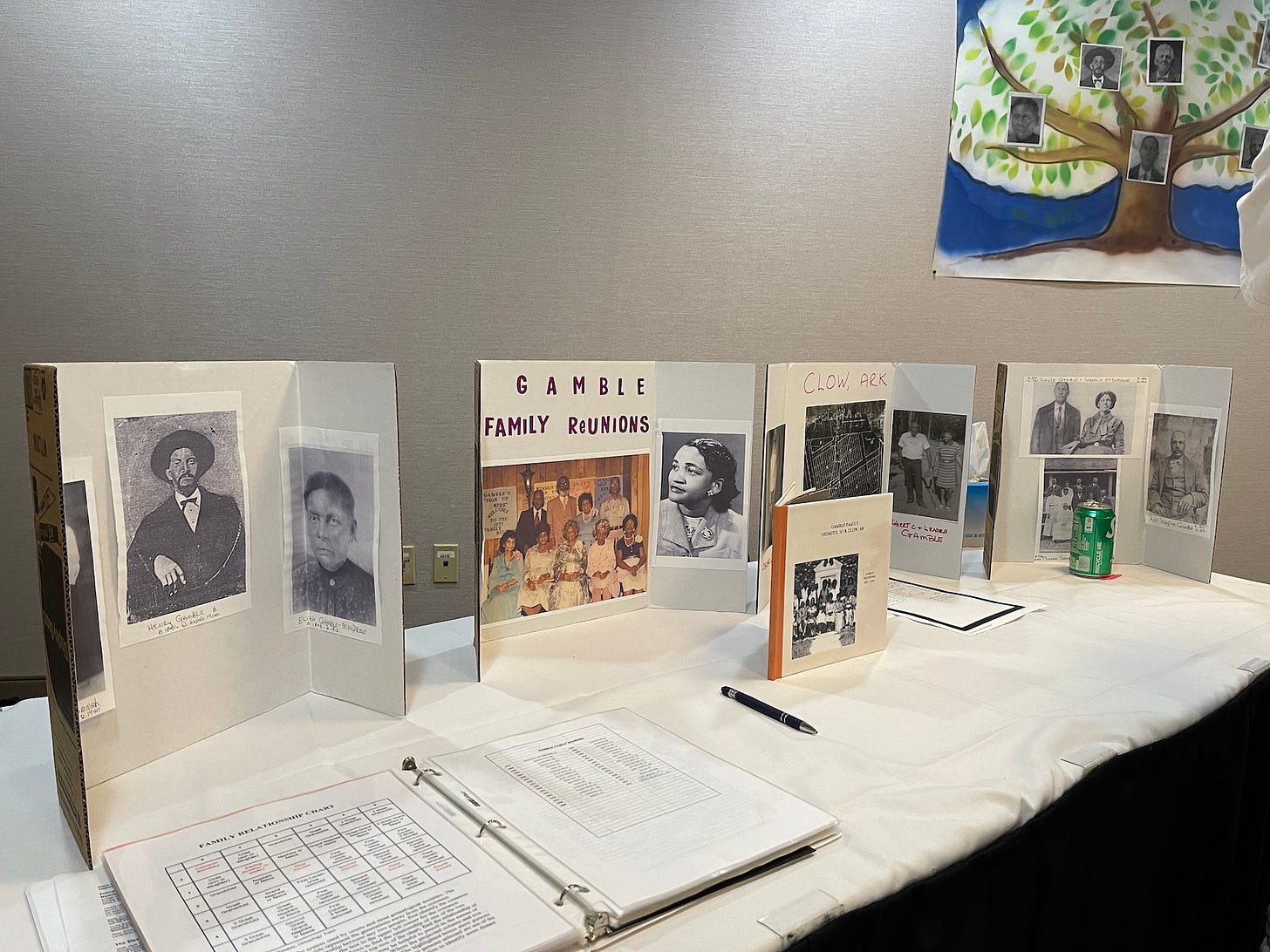

After that we drove out towards the airport to stay a few nights at the hotel where the Gamble family reunion was being held. It was a small gathering. In pre-pandemic times reunions were attended by up to 300 people, but this year there were 45 or 50 attendees. I was excited to finally meet Raimonda Martin in person. She was one of the original founders of the family reunions, and author of an amazing and well-researched genealogy book about the Black Gambles. She had started her research in the 80s, when many elders were still alive, confirming oral family histories that went back to slavery days. Without Raimonda I wouldn’t know as much as I do about my ancestors. I’m so grateful to her and her work.

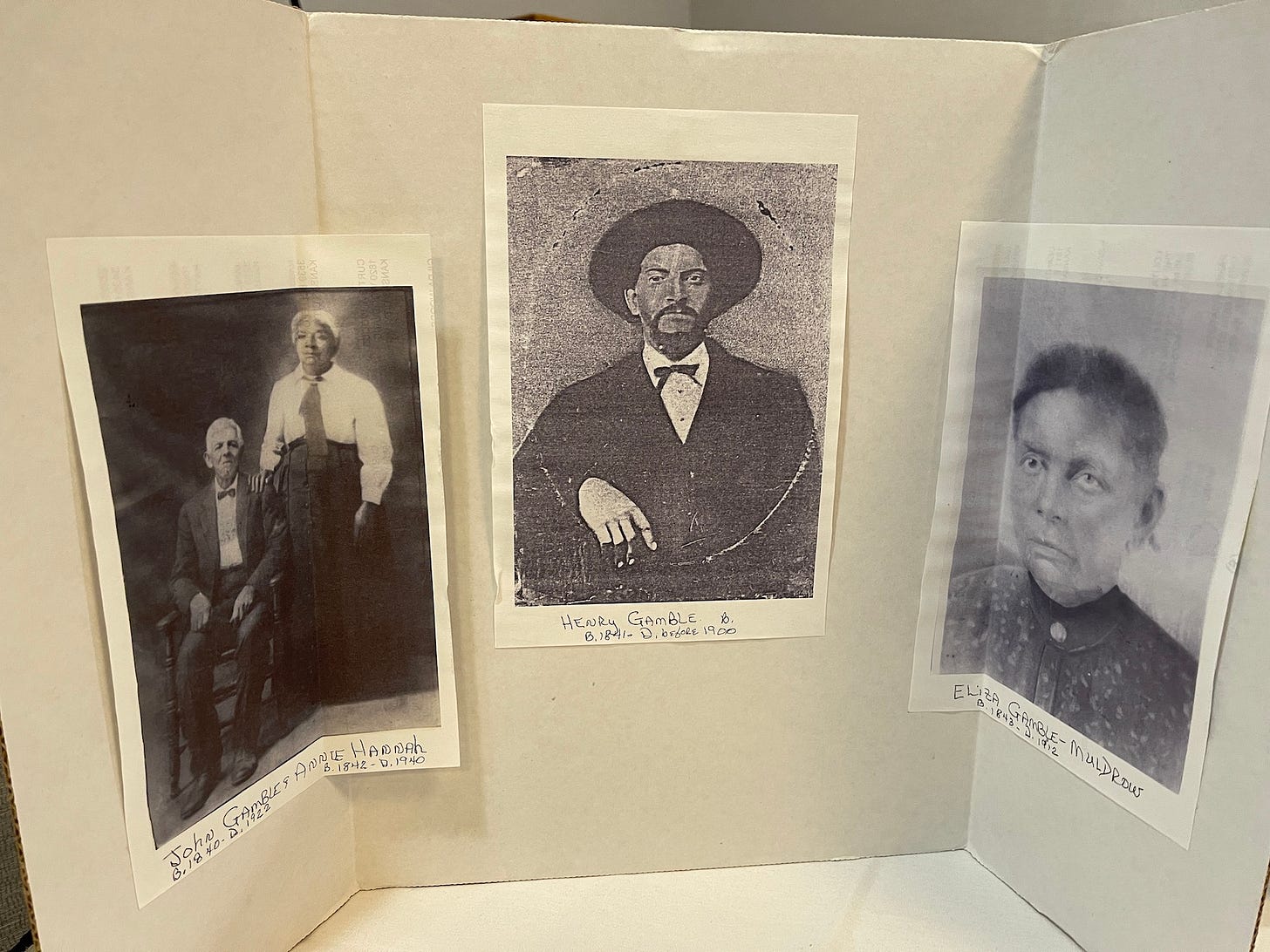

When we checked in, we were each given a t-shirt that had photos of the seven siblings who were the children of slave mother, Mary. Mary was the daughter of Lizette Gamble, my fifth great grandmother – whose name I miraculously share despite my adoptive parents having absolutely no knowledge about my biological family and history.

These seven siblings were all enslaved by the White Gamble family. They were left in a will to the slave master’s children, and were brought to Arkansas when some of the Gamble sons bought property there right before the civil war. My family descends from John Gamble, one of the seven siblings. He looks pretty much like a white man (I know I don’t have to explain why). John Gamble lived the rest of his life in Arkansas. His offspring did as well, including my grandmother. Even my biological father and uncle were born in Arkansas – although they left when they were very young.

The next day, after getting settled and meeting many cousins for the first time, we donned our new t-shirts and boarded a tour bus to drive the hour and a half up to Nesmith. They gave us navy blue face masks to match our shirts. On the front of the t-shirt, above the photo of the siblings, it read “We stand upon our ancestors’ hopes and prayers.” And on the back, it said “We are the dreams of our ancestors.”

I had so many feelings on that bus, seeing those words on t-shirts all around me, worn by people who were all my biological cousins. People I had never met before, but who like me descended from enslaved people who had made it through the unimaginable. As an adoptee, I had never imagined I would get to have this experience. I never thought I would know who my birth parents were, let alone meet distant cousins. Being on a bus with them, headed towards the land where our ancestors toiled and worked in this hot, brutal yet lush climate, was simply unbelievable.

The heat. I keep talking about it. The South Carolina heat is no joke in August. You really can’t stay in the sun – it’s almost intolerable, especially with the humidity. Then to imagine working outside as an enslaved person…. I just kept thinking of the strength and resilience that it would require. Sheer fortitude. And how many I’m sure didn’t make it. I was being given a deeper understanding of what my ancestors went through – one I wouldn’t have fully grasped if I would have come in the winter. Because of that I was glad to be in the heat. I could feel the truth of things in my bones.

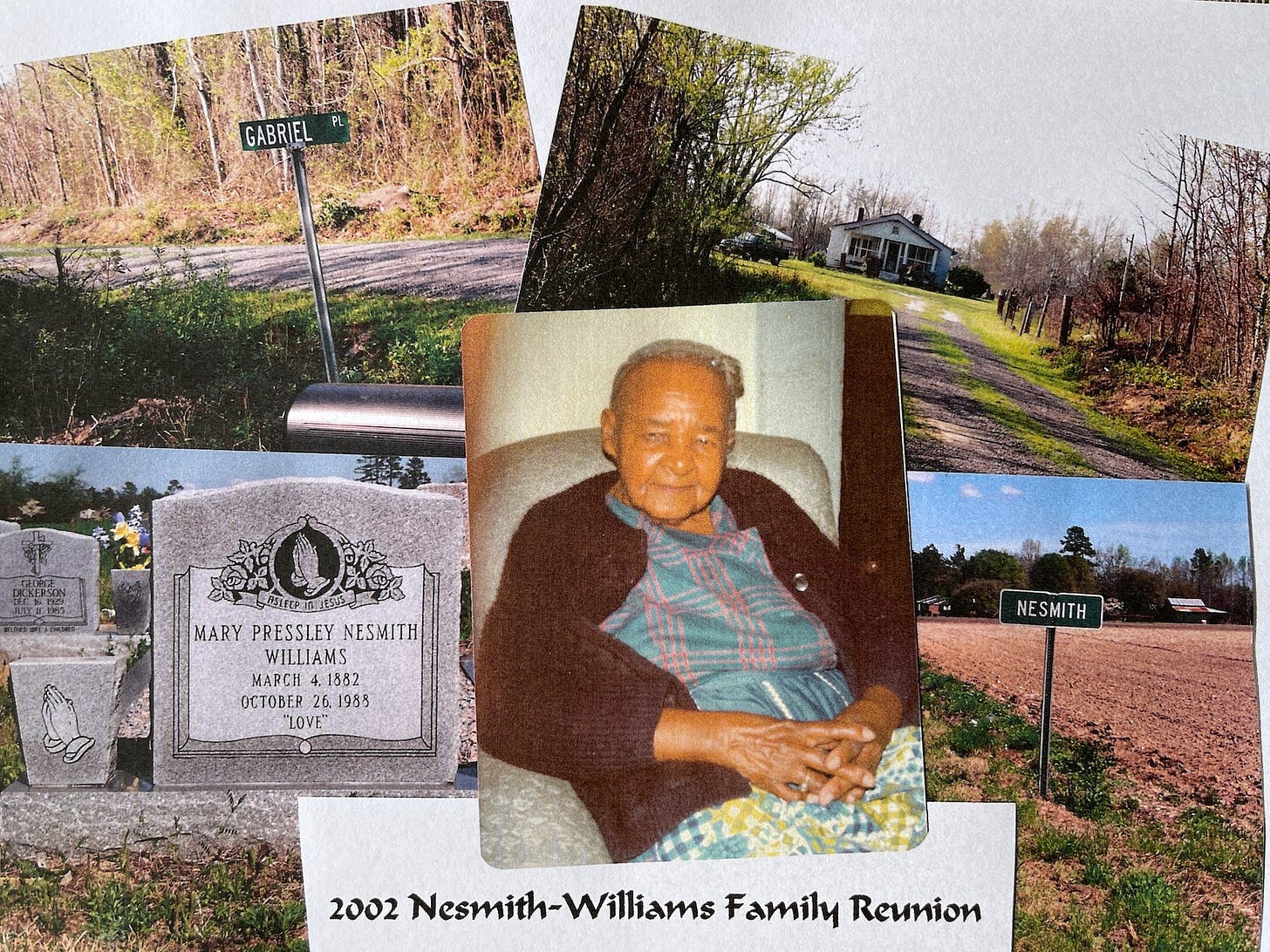

Once we reached Williamsburg County, we first drove by the land where our ancestors once worked tobacco and cotton fields. We then briefly stopped at a church in Nesmith that had been built by one of the original seven siblings. We took a group photo then headed to the Black-owned Williams Muscadine Vineyard to use their bathroom. It turned into an unplanned and meaningful experience.

Some of us ended up under a ramada next to an old dilapidated farmhouse, sitting and fanning ourselves in the heat. One of the owners, a woman named Cassandra, offered to share the history of the area and her vineyard. She apparently also has started a local museum dedicated to Black history in Williamsburg County. We sat rapt with attention as she started sharing stories and memories.

The grapes had been planted by her father David Williams, who was the son of Mary Pressley Nesmith Wiliams. Mary’s family had been given the land after slavery ended, and initially they still grew tobacco and cotton. But Mr. Williams had the idea to plant grapes in his later years, and many decades later it is a thriving vineyard.…its special Muscadine grapes known for their flavor and health properties. This was the story of many local Black families. The white families had left after slavery, selling or giving the land to the Black people who actually knew how to grow the crops.

Cassandra told fascinating stories about her grandmother Mary, including that she had died in the historic old home next to us (Cassandra herself had been born in the same house). Mary had become a widow with 11 children, and then married a widower with 10 children. They had one child together – for a total of 22 children. At one point up to 19 people had been living in that small farmhouse, now an official heritage site.

That moment of storytelling was priceless to me. We couldn’t go to the home where our ancestors lived, but here we were just down the road hearing a similar family story while listening to the crickets, taking in the rich smells and feeling the thick heat. I’ll never forget it – sitting with my cousins and listening to stories of the past. It cemented for me why it’s important to travel to the places where your ancestors lived. It gives a perspective and understanding that you simply can’t get any other way.

I will be returning to South Carolina, and digging further into its history. It feels like this is just the beginning of my relationship to this place, with its deep connection to Sierra Leone, one of my African homelands. This trip felt like the perfect starting point for my Traveling My Roots project. It was meant to be.

This post 2022 Gamble Family Reunion in South Carolina appeared first on Traveling My Roots.